September 17 2019 10:00 | Sala Valle Inclán, Círculo de Bellas Artes

Speech of Muhammad Khalid Masud

In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

Attacks on places of worship have a long history. Not that the history should justify their continuity but I mention it to express worry about their rise in the modern period. It is particularly outrageous today when we acclaim autonomy of the self and freedom of religion as the pride goals of modernity. It is irritating that our focus on war on terrorism has only accelerated hatred and terror against religion and religious pluralism.

Pew Research Centre, in its report in 2016, observed that attacks on religious sites are part of a global rise in the anti-religious sentiment among individuals and governments. The report found noticeable increase in hate crimes since 2001. In 2007 the level of social hostility involving religion was 20 %; in 2016, but it increased to 27%.

In 2019, attacks on al-Noor Mosque in Christchurch on 15 March, on churches in Colombo on 21 April, and on Chabad of Poway Synagogue, on 27 April shook everyone concerned to question what was happening. CNN raised and discussed these events with the following questions as title of a news story in the last week of April: Are Muslims and Christians at war? Hate Crimes in Houses of Love? and Houses of Worship Worry: who's next?

Based on University of Maryland Global Terrorism Database, News 18, India, reported on 25 April that 24 % of all terror attacks on places of worship worldwide between 2000 and 2017 happened in South Asia region. Significant increase in such occurrences has been continuously noticed since 2012, but these attacks accelerated in 2011. Mosques were the most attacked places and Pakistan was the most affected country in the region. Hate crimes in the US alone were 17% in 2017. In Pakistan, a decade of sectarian violence preceded the 2001 terrorist attacks.

CNN repot on 29 April analyzed the socio-political context and observed a cancer like movement of white supremacists spreading in the US and other developed countries. The worry was the failure even to recognize this danger. These supremacists want to keep their country 'pure' and religiously monolithic. Religious pluralism is considered the biggest challenge all over the world. Supremist nationalism expresses itself in the most fundamental and pure forms against all kinds of pluralism, including the religious one. It is the failure of modern statism against pluralism that freedom, so much required by the concept of democracy and the autonomy of the self, feels threatened.

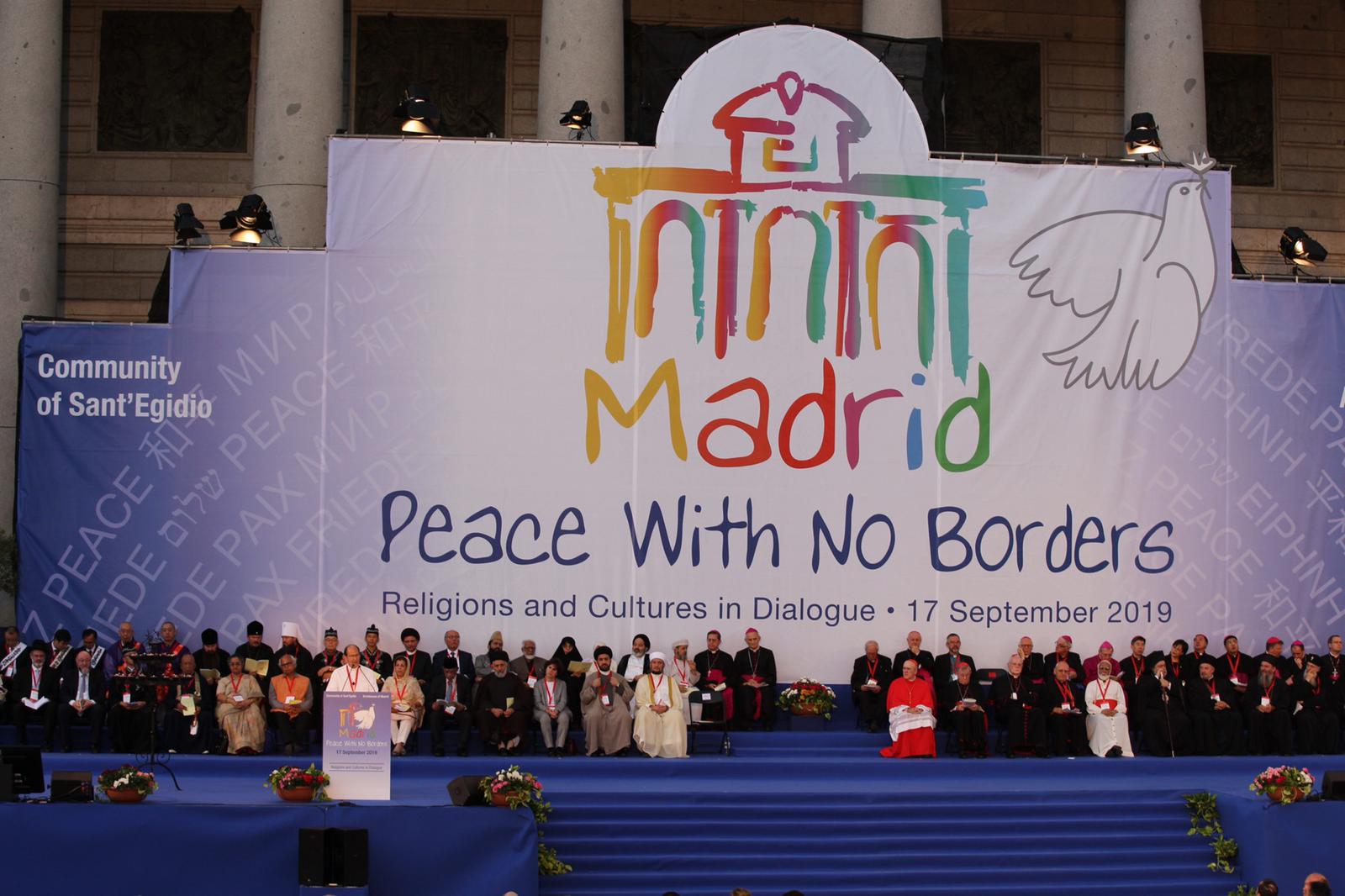

I must congratulate the Community of Sant'Egidio for raising the banner of peace and bringing cultures and religions to dialogue to address these critical issues. The Community has successfully negotiated peace between various communities, religious and cultural, in Asia, Africa and Europe during 1987 and 2017. The Community has been holding successful international meetings every year since 1986 on various peace themes.

I should specifically mention here the role of the Community as peace maker in Mozambique. The Community of Sant 'Egidio worked persistently for four years from 1988 to 1992 for ending the war in Mozambique that had been going on for 16 years and in which one million people had died. The Community finally succeeded inviting the Government and rebel fighters to the Community's House in Rome to sign peace document in 1992 to end this long war.

This year the theme "Peace with no borders" initiates a well-timed subject for discussion when the whole world, or parts of it, is moving towards globalism. Most of the present-day problems have arisen out of one or the other kind of borders, physical, imagined, social, nationalist and religious. Borders become more problematic when they assume the status of markers of ideology and identity and motivate individuals and groups to attack places of worship, the topic for this panel.

Attacks on places of worship disclose fear of religion and much more. They unveil the utmost fear, hatred and a sense of inner insecurity against the worshipers who are in the most vulnerable positions in synagogues, churches, mosques, temples and other places of worship. In the words of Daniel Burke, the CNN religious editor,

"There is something uniquely disturbing about violence in sanctuaries … Because sanctuaries – temples, mosques and churches -- are not just consecrated buildings. They are sacred in another sense as well. Temples and mosques and churches are sites of refuge from the world, places where the soul can seek safety, havens free from hatred. When believers bow their heads in prayer, they make themselves, intentionally, vulnerable. Their thoughts are tuned to the eternal, not to clear and present dangers. If, after these relentless attacks, houses of worship become surrounded by barbed wire and policed by armed guards, that sense of sanctuary will have been lost, and may never be regained".

The Quran questions, "And who does greater evil than he who bars God's places of worship, so that His Name be not rehearsed in them, and strives to destroy them?" Quran 2: 214.

I want to relate attacks on places of worship and the present-day fear of religion, and hatred on the one hand and terrorism, fundamentalism and extremism on the other hand to a very serious crisis of identity. It is the product of conflict between universal values and local hegemonic perspectives. In early twentieth century, several thinkers noticed the problem and warned about the direction that the crisis of national identity would take. Muhammad Iqbal in India wrote about it in 1923.

"The growth of territorial nationalism, with its emphasis on what is called national characteristics, has rather tended to kill the broader human element in the art and literature of Europe". (Iqbal 112). He argued, "Just as the universal character of scientific truths engenders werities of scientific national cultures which in their totality represent human knowledge, much in the same way the universal character of Islamic verities creates varieties of national, moral and social ideals. Modern culture based as it is on national egoism is only another form of barbarism". (Iqbal 124) . I am sure he referred to the ignorance of diversity and pluralism.

Wars have continued, ethnicity has transformed into racism, powerful states are claiming exception to the concept of universal and international laws. Religious, moral and ethical values have lost their universality. We are moving toward globalism as well as to religious pluralism but each wave of globalism is taking us to new expressions of diversity and pluralism. Instead of appreciating, we are responding to Globalism by reinterpreting it in hegemonic terms.

I see attacks on sanctuaries, the places of peace by extremists, terrorists, supremacists, fundamentalists as hatred of and war against diversity and religious pluralism. Focus on territory, ethnicity, language, race and nationalist ideologies as markers of political unity marginalizes religious affiliations. Added to this crisis are the issues of religious minorities and legal pluralism. The situation produced an identity crisis, which is now called 'dissociative identity disorder'. It calls for care and treatment of those who are suffering from this disorder.

Hatred against religion is the consequence of all these developments that need urgent attention. The way forward lies in universal values of peace, not in war; in cooperation, not in hegemony. We must promote interfaith dialogue to honor religious pluralism. We need global ethics of universality, care, responsibility and kindness. We must have respect for differences and human dignity.

Let me close it with the prayer in the words of Abraham that he spoke after building the sanctuary of Ka'ba in Mecca several centuries ago, "My Lord, make this a City of Peace, and feed its people with fruits,-such of them as believe in Allah and the Last Day" (Quran, 2: 126).

Amen.